Exeter City Council is set to seal the fate of Northbrook swimming pool at a meeting of its executive committee tomorrow evening, when it is expected to decide to close the pool, for the second time, on the basis of a report produced by council director Ian Collinson.

The council is apparently intent on ignoring the outcome of a special scrutiny meeting that is being held tonight after campaigners presented a petition signed by nearly 2,250 local residents imploring it to keep the pool open at a full council meeting at Exeter Guildhall on 10 June.

At that meeting, council members unanimously agreed a motion proposed by opposition co-leader Diana Moore that the council “refers the petition to a scrutiny meeting for consideration prior to the executive determining the matter, and that the petitioners, officers and Northbrook Trust are invited to present their case and evidence to that scrutiny committee”.

Ian Collison also produced a report for this meeting. It runs to 109 pages, only the first five of which differ slightly from the contents of his 109-page report to Tuesday’s executive committee meeting.

Both reports are titled: “The Proposed Closure of Northbrook Swimming Pool”. His scrutiny report says it has been produced “to advise members on the impact of the proposed closure of Northbrook swimming pool” despite the full council’s decision on 10 June to hold tonight’s scrutiny meeting to consider the petition, which is not to close the pool but to keep it open.

There is no sign that Northbrook Community Trust, a charity which supports disadvantaged children and young people and which owns the building’s freehold, will attend either meeting.

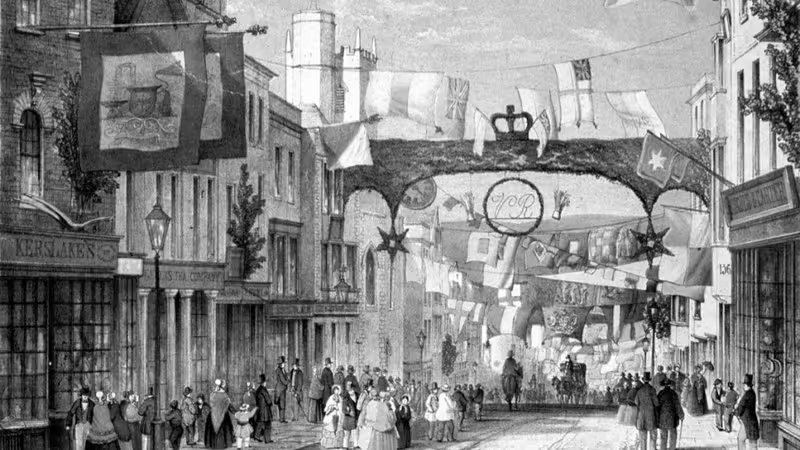

Northbrook pool. Photo: Exeter City Council.

Northbrook pool. Photo: Exeter City Council.

The arguments that Ian Collinson attempts to present in favour of Northbrook pool’s closure boil down to two principal issues.

One is that the pool requires a subsidy to cover an income shortfall resulting from low usage levels despite what he describes as “extensive efforts to drive income and footfall”.

The other that the building needs capital investment to bring it up to scratch, in particular to provide “disabled access and increased toilet and changing facilities”, which the council says it can’t afford.

Referring to the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 under the heading: “Are there any other options?”, both his reports say: “If Northbrook swimming pool were to remain open a minimum of £2.1 million investment from the council will be required to maintain and improve the facility and make the facility DDA compliant”.

They add: “Further investment would also be needed to increase revenue and use across a wider geographic area, which would result in an increase in operational costs related to staffing and extended opening hours.

“Given these significant expenditure requirements, it is evident that Northbrook swimming pool necessitates substantial investment to remain operational. Without this investment, it will not be sustainable to continue operating the facility in its current state.”

The trouble with all this, apart from both reports betraying the pretence that the decision to close the pool wasn’t made in February in repeated tense slips, is that they that they fail to prove either argument.

As a detailed and wide-ranging report produced by the Save Northbrook Pool campaign in advance of this evening’s meeting puts it, councillors “will see that what has been presented as fact is overly-simplistic and quite definitely not true.”

Northbrook pool, believed to be in the 1920s. Photo: Michael Davey.

Northbrook pool, believed to be in the 1920s. Photo: Michael Davey.

Ian Collinson’s reports are accompanied by three appendices, the first of which contains another eight appendices, followed by two remaining appendices which are separately attached to each report.

To say that the way these documents are presented muddies the waters is to be charitable. Each lead report contains eleven references to “Appendix A” despite each of these references being to one of eight sub-appendices that are included with appendix A.

This leads with a two-page summary of another eight appendices, and itself refers to them as A to H.

The first of these is not the appendix A attached to each lead report, but a second appendix A. There are also two appendix Bs and Cs – and also two appendix Gs, because one is mislabelled and should be labelled H instead.

The appendices are also disjointed, so that those addressing subsidy issues are, for example, included as sub-appendices A, B, E and F and those addressing the pool’s capital investment requirements are included as sub-appendices D, G and the second appendix G.

There should also be an appendix addressing capital investment requirements around Equalities Act compliance but there is none. No explanation is provided for its absence.

Sub-appendices A, B, E and F are supposed to address the issue of Northbrook pool requiring a subsidy to cover the shortfall between the income the council records for the facility and the day-to-day expenditure associated with keeping it open.

However this issue can only be approached by first understanding how the council records income from leisure service memberships.

Instead of apportioning the income from monthly membership receipts to each of its six leisure centres according to centre use, it allocates it according a “home” leisure centre recorded for each member when they sign up, even though all (non-spa) memberships confer access to all six centres.

The problem with this approach is that St Sidwell’s Point is automatically allocated as each member’s “home” leisure centre unless they actively choose otherwise during the sign-up process.

Once a “home” centre has been set, leisure services users cannot change it themselves. The council says that the only way it can be amended is “back of house on the management system” when a member submits a manual request to council staff.

On its own, this would be misleading enough as both a centre usage metric and a way of calculating centre income. It becomes even more so when you realise that the council accounts for about three-quarters of all its leisure services income this way.

The remaining income is made up by a combination of pay-as-you-go uses, classes and hire which takes various forms in each leisure centre. At Northbrook it is as impossible to account for this properly as there are no turnstiles or other means by which the council can collect reliable data. Instead, lifeguards carry out occasional head counts.

As a result, all the claims made about Northbrook pool income in Ian Collinson’s reports are necessarily inaccurate. They are also scant, and presented in inconsistent and misleading ways.

2022-23 Exeter Leisure centre net revenue subsidies & debt repayments. Source: Exeter City Council.

2022-23 Exeter Leisure centre net revenue subsidies & debt repayments. Source: Exeter City Council.

The income the council has allocated to Northbrook pool is presented in the June 2025 lead reports as a total “since 2020” despite the fact that the council did not begin re-opening its leisure facilities following pandemic closure until April 2021.

Sub-appendix A confirms this, while also confirming that the figures only cover the period to December 2024.

The same is true for the usage figures claimed in Ian Collinson’s lead reports, which say they are correct “at the time of writing” even though sub-appendix B confirms they were actually correct last December, six months earlier.

The reports also rehearse another council pool usage nostrum, that all of the members it has allocated to Northbrook “benefit from access to other council-run swimming pools, including Riverside Leisure Centre and St Sidwell’s Point”. The council never says that all the members it has allocated to St Sidwell’s Point or Riverside also benefit from access to Northbrook.

The Save Northbrook Pool campaign says that when it asked the council to provide detailed information on actual leisure centre use, broken down into categories to differentiate swimming from other uses and separated into visits by monthly members and pay-as-you-go users, it refused.

The council’s day-to-day expenditure figures ought to be more reliable: it should know who it is paying to work where and to which facility energy or maintenance costs, for example, apply.

They should be more transparent, too. But the figures it provides in sub-appendix F omit depreciation, a significant factor at St Sidwell’s Point where this cost the council nearly £630,000 in 2023-24 alone. Northbrook depreciation was £25,291 in the same year.

Ian Collinson’s reports then quote a total Northbrook pool income shortfall subsidy figure of £686,000 which they also say is “since 2020” and “to date”. Income shortfall subsidies and debt repayments for St Sidwell’s Point, when depreciation is included – as it is in the council’s accounts – came to more than £3.2 million in the two years from April 2022 alone.

Without leisure service-wide figures to properly compare Northbrook with the council’s other leisure centres, covering accurate annual income and expenditure, including maintenance and repairs, which came to an annual average of only £17,800 at Northbrook according to sub-appendix E, it is impossible to make an informed decision about the future of Northbrook pool.

2023-24 Exeter Leisure centre net revenue subsidies & debt repayments. Source: Exeter City Council. 2024-25 figures will be published in July.

2023-24 Exeter Leisure centre net revenue subsidies & debt repayments. Source: Exeter City Council. 2024-25 figures will be published in July.

Moreover, as the Save Northbrook Pool campaign says: “The absolutely vital concept to grasp is that swimming pools do not succeed or fail just on the numbers of individual people who turn up to swim. To survive, all swimming pools require a mix of income from many different sources.

“They must have hires to outside organisations, whether schools or clubs or parties; they must run profitable classes, such as Aquafit, or classes for the elderly or swimming classes; they may have a café or a function room; and they need to charge what their competitors are charging, to swimmers and to hirers.”

Ian Collinson’s reports do touch on the topic of pool marketing, but only barely, and they don’t address any of the points the campaigners make about income mix.

Sub-appendix C provides a table summarising what the lead reports trumpet as “a total of thirteen targeted sales and marketing campaigns” that were “aimed at attracting new members and increasing engagement from existing users”.

What the reports don’t say is that seven of these “campaigns” only ran for a week or less, and another two only ran for a fortnight. And they don’t explain the limitations of relying primarily on digital platforms to promote them or that each campaign’s “reach” figures are irrelevant. It’s results that count, for which poor council marketing is to blame, not Northbrook pool users.

Ian Collinson’s reports describe this as “sustained promotional efforts” before complaining that “growth in both usage and revenue has remained limited” then adding that this issue “forms a critical part of assessing the future viability and strategic direction” for the pool.

Northbrook pool timetable, June 2025. Compiled from original.

Northbrook pool timetable, June 2025. Compiled from original.

His reports also fail to acknowledge the impact of Northbrook’s very restricted opening hours. The pool is open for less than 42 hours each week, compared with 89 at St Sidwell’s Point, and is only available for lane or general swimming for 23 of them.

The Save Northbrook Pool campaign sought guidance from Swim England on this issue. It was told that normal opening hours for a well-run swimming pool, notwithstanding differences between facilities, would be 7am-9.30pm on weekdays, 7am-10pm on Saturdays and 7am-5pm Sundays, with some closing later to allow for club hire.

Northbrook closes at 3pm on weekdays, before children come out of school, and is only open at the weekend on Saturday mornings. It is closed altogether on Sundays.

The Save Northbrook Pool campaign says that were the pool open for longer hours, as it used to be, and run as a “proper functioning swimming pool”, it might well increase its income to the point that it became, uniquely among council leisure services facilities, close to self-financing.

It also points out that the council’s leisure services budget ended the 2024-25 financial year with an underspend of £874,000.

While £646,000 of this was income from an HMRC VAT refund, and expenditure on salaries was £200,000 lower than expected because of recruitment difficulties, income exceeded budget by £290,000 – enough to cover the Northbrook operating subsidy for nearly two years, even with all the restrictions the council has placed on it.

Ian Collinson’s reports appear to admit that there has been a lack of investment in increasing Northbrook pool income when they say that investment in marketing would bring an “increase [in] revenue and use across a wider geographic area”.

But rather than develop a renewed business case for the pool – a document which is also conspicuous by its absence and with which Swim England has said it would help – they instead warn that increasing the number of people using the pool would mean “an increase in operational costs related to staffing and extended opening hours”.

Northbrook pool timetable, May 2020. Scan from original.

Northbrook pool timetable, May 2020. Scan from original.

Various appendices bundled with Ian Collinson’s reports address the other principal issue facing Northbrook pool: the need for capital investment to bring the building up to scratch.

Under the heading “Ongoing maintenance issues”, all that the briefing report attached to the lead reports says is: “There are several current maintenance issues ongoing at Northbrook swimming pool”.

Sub-appendix D, to which it refers, offers a little more detail but nothing to say about the potential cost of remedial works.

Instead, the briefing report includes a single-sentence claim that “general repair maintenance is no longer sustainable, and the centre needs extensive whole building repair works”. This is followed by three single-sentence summaries which, combined, claim that the building needs capital investment of at least £2 million.

It refers to sub-appendix G to account for £850,000 of this total and sub-appendix H (also lettered G) to account for another £700,000.

But it then simply states that the pool also needs another £450,000 to £550,000 to “ensure the building meets the requirements of the Disability Discrimination Act by providing a disabled changing room and platform lift”.

It does not provide any explanation of or evidence to show how this cost estimate has been derived: an omission which appears to show that the council has simply concocted the figures.

Nor does it explain that this 1995 Act has been repealed (except in Northern Ireland) and replaced by the Equality Act 2010, or appear to recognise changes in the council’s obligation under the new legislation.

If the council has kept Northbrook pool open for the past thirty years, since applicable equalities legislation was introduced in 1995, why must it suddenly be closed now?

The Save Northbrook Pool campaign says that, while access to the pool building as it stands is “not ideal for those with mobility issues, Northbrook being on a slope and covering two floors”, the needs of these people “must be balanced with the needs of others” protected under the newer legislation.

These include people with emotional or behavioural issues such as children at Ellen Tinkham School, which sends many of its pupils to Northbrook to provide them with opportunities to swim.

Ian Collinson’s reports have nothing to say about this issue at all.

Northbrook pool decarbonisation strategy report (sub-appendix G). Source: Exeter City Council.

Northbrook pool decarbonisation strategy report (sub-appendix G). Source: Exeter City Council.

In contrast, sub-appendix G provides plenty of detail on the capital investment proposals it covers. But rather than providing the options appraisal for “extensive whole building repair works” that might be expected, it turns out to be a report that the council commissioned in order to apply for government decarbonisation funding in 2023.

As the report says, its purpose was to address the “energy upgrade and carbon reduction opportunity” provided by the Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme to enable the council to apply for a grant. Not to establish Northbrook’s general capital investment needs.

(In the event, the council applied for funding to pay for decarbonisation upgrades at Riverside Leisure Centre and RAMM instead. It secured a £6.4 million grant towards £7.3 million project costs, then pulled out. The government subsequently axed the whole scheme earlier this month.)

Nevertheless, Ian Collinson’s reports present the £850,000 decarbonisation upgrade project as if it is essential to the viability of Northbrook pool. This costly project is by no means the only option the council would be considering if it was approaching the pool’s future with an open mind.

Instead, it is ignoring the fact that the report covers other options that may well be more viable, because the decarbonisation plan it proposes may not be viable at Northbrook at all. Why? The report says decarbonising Northbrook the same way as the council intended at RAMM faces the same grid constraints that limit the local electricity supply.

Northbrook pool energy consumption benchmarking analysis. Source: decarbonisation strategy report.

Northbrook pool energy consumption benchmarking analysis. Source: decarbonisation strategy report.

Ironically, the report’s energy consumption benchmarking analysis also finds that Northbrook is already performing better than a typical swimming pool installation, although the building certainly needs a wide range of fabric upgrades and plant replacement to make it viable for decades to come.

What it also says is that, instead of spending £608,300 on the installation of an air source heat pump and photovoltaic panels to go with it, the “like-for-like cost of a replacement conventional fossil fuel system is £24,185”.

All the other building fabric upgrades that the report recommends, which include significantly improving its energy efficiency by replacing its roof, walls, windows, doors, roof-lights and lighting systems, would cost around £300,000.

This option isn’t mentioned anywhere in Ian Collinson’s reports, which present the full-fat £850,000 decarbonisation option as if no other choice exists, without acknowledging that it might not even be possible because of grid constraints.

Nor is the council saying that it should close all the other many buildings for which it is responsible that do not have state-of-the-art low carbon heating systems because it cannot afford the upgrades.

However it is currently replacing combustion engine-powered vehicles in its fleet with more combustion engine-powered vehicles, rather than electric vehicles, because the latter cost so much more than the former.

Northbrook pool condition survey report (sub-appendix H, mislabelled G). Source: Exeter City Council.

Northbrook pool condition survey report (sub-appendix H, mislabelled G). Source: Exeter City Council.

A Northbrook pool building condition survey report in sub-appendix H (mislettered G) also provides plenty of detail on the capital investment proposals it covers.

But it includes costs for all the building fabric upgrades and the like-for-like heating system upgrade that are already covered in the decarbonisation report.

These duplications equate to around £182,000 of the works costs it estimates.

When the works in the two reports are combined, the total comes out at around £950,000 instead of the £1,550,000 Ian Collinson’s reports claim. Several substantial plant replacement costs are also included which may not even be necessary. It’s not clear, for example, why the council needs to spend £32,300 on “data replacement” at the pool.

And the condition survey recommends performing the works over the course of fifteen years, with total expenditure of £32,000 required in year one and another £66,000 over the following two years.

Even if the total capital investment requirement to transform Northbrook pool into a modern, conventionally-heated but energy-efficient facility is somewhere around £1 million, this only equates to an average of around £66,000 each year over those fifteen years.

This is less than half of the “minimum of £2.1 million investment” that Ian Collinson’s report says is required to keep the pool open.

Northbrook pool closure consultation report (appendix B). Source: Exeter City Council.

Northbrook pool closure consultation report (appendix B). Source: Exeter City Council.

The gulf between reality and Ian Collinson’s recommendations gets wider when it comes to the results of the public consultation that the council belatedly began in March and the mitigations he proposes to address the equalities impacts it identifies.

The consultation report (appendix B) first admits that the consultation limited itself to directly contacting only the 83 people that the council considers to be Northbrook members, rather than all the council’s leisure services users, to invite them to participate.

Curiously, it then says more people who said they were Northbrook members responded to the consultation than it says is possible because of the way it accounts for leisure centre memberships.

Its findings are presented under three themes. It confirms that Northbrook pool plays an important role in people’s lives, not least because of its importance in educational provision of swimming lessons but also because the pool acts a community hub.

It also says the pool’s closure will have an impact on people’s lives because they will no longer swim for exercise or as a hobby, with attendant social and support network losses, and it confirms that there are multiple barriers obstructing access to other council pools.

Its conclusions are clear. It says: “If the pool closes, it will have real-world impacts” on many of its users, and that “among the 322 people who took part, older people, school children (including those with SEND), carers, and lower-income families are likely to be most impacted by a closure.”

It continues: “While some barriers people face to access a different swimming pool in the city (St Sidwell’s Point and Riverside), may be overcome by working with particular groups (e.g. schools) to find a resolution, other barriers would be difficult to overcome.”

It says this is because of issues that are “deeply connected to people’s life experiences, such as affordability, mobility issues, and time associated with travelling further distances with the city. Additionally, other barriers fall outside of the Councils control, such as unreliable public transport”.

It adds: “There are limited options to drive improvement.”

Northbrook pool closure Equality Impact Assessment (appendix C). Source: Exeter City Council.

Northbrook pool closure Equality Impact Assessment (appendix C). Source: Exeter City Council.

Ian Collinson’s reports seem to acknowledge these findings at first: “The council recognises that the proposed closure of Northbrook Pool does have an impact on certain user groups, specifically in relation to disability, sex, age and neurodiversity as referred to in the consultation report.”

They add: “The council is committed to taking appropriate steps to mitigate these impacts as part of the transition plan and to ensure that the needs of affected groups are considered as part of the decision-making process.”

But this “transition plan” is nowhere to be found. Instead, the council says it will “carry out a full audit of current activity within the leisure portfolio to identify potential gaps in provision for all protected characteristics”. It does not explain why it has not completed this audit and provided councillors with its findings before asking them to close the pool.

The Equalities Impact Assessment that follows (appendix C) is even more evasive.

Its section on the negative impact of the closure on people with disabilities initially admits that the health and well-being impacts for those with a disability who use the pool include “physical impacts in relation to general health or managing their condition as well as mental well-being impact if social interaction was lost”.

It continues (in full): “Northbrook swimming pool was reported to be a lifeline to some users in difficult and trying times in their lives, whilst others reported they had come to depend on the swimming pool in supporting their routines for positive mental and physical health.

“People with neurodivergence reported that Northbrook swimming pool was a welcoming place that helped them tackle loneliness and isolation. People with disabilities who use Northbrook swimming pool also felt more reluctant to use alternative centres due to their larger size.

“The other swimming pools in the city were reported as intimidating, overwhelming and anxiety-inducing by some respondents, with a sense that these issues would be exacerbated for those with mental health conditions or those with neurodivergence.

“People with disabilities reported that the small size of Northbrook meant they felt more comfortable and more able to use the facility as it is quieter and more personal.

“During the consultation, of those who stated they suffer from a long-term health condition, a number of responses indicated that it was daunting to think about joining another leisure centre and that it wouldn’t be easy to travel to alternative provision.

“Furthermore, it was also reported that the closure of Northbrook swimming pool would also impact SEND children who use the swimming pool for lessons as Northbrook provides a quieter environment which is beneficial to their needs.”

How does Ian Collinson propose to address these impacts? By simply signposting Northbrook users to “alternative provision” and carrying out a leisure services audit.

Exeter City Council facilities report. Source: Swim England.

Exeter City Council facilities report. Source: Swim England.

It’s the same story with negative Northbrook closure impacts on people because of their sex. More females than males use the pool and confirm they would have trouble accessing other facilities. Apparently a council audit will solve this problem too.

When it comes to negative age-related closure impacts, which will affect children and young people, young mothers and families and older people in particular, the impact assessment has so many issues to report that it is subdivided into several sections.

The “mitigating actions” that follow are few, feeble and framed by weasel words that leave the council committed to very little beyond its cure-all audit which, of course, cannot be a mitigating action in itself.

There is apparently “potential scope” for children’s swimming lessons elsewhere, future leisure service priorities will be identified “within available resources”, as-yet-unwritten travel plans will “maximise accessibility” of other pools and “familiarity sessions” will help people overcome their ills.

The council will even “consider costs” at its other leisure centres.

Then the legal summary section of Ian Collinson’s reports reminds their readers: “Where a public consultation process is undertaken, then the responses must be conscientiously taken into account before a final decision is made”.

It adds that the council’s Public Sector Equality Duty “must be exercised with rigour, in substance and with an open mind” and that decisions must be “informed by the required due regard”.

It nevertheless concludes: “The council has taken time to consider the potential impact of closure on these groups and is confident that some provision within other centres can be offered; providing a suitable, safe environment”.

To make matters worse, the reports also re-frame the results of the council’s 2025-26 budget consultation, which it previously said found only 30% of respondents agreeing with the council’s proposal to “reduce the subsidy on the six council run leisure facilities”.

47% of the respondents disagreed, in an interviewer-led survey which the council repeatedly said would accurately represent the views of the whole city. More than half of those who voluntarily completed the online version of the survey also disagreed.

Apparently now, “on further analysis”, the council finds that there was “higher agreement on reducing the subsidy on the six council run leisure facilities amongst those aged 65 or over, females, non-white ethnic groups and Exeter City Council housing tenants”.

But it also finds “higher disagreement from younger people aged 24-44, males, those from a white ethnic background and those who did not have a disability or long term condition and those living in areas of lower deprivation”.

It doesn’t explain why this might be relevant, although the implication seems to be that, somehow, this means that many of those identified as likely to suffer inequalities impacts as a result of closing the pool probably want it shut anyway.

Extract from What makes St Sidwell’s Point such an asset. Source: Exeter Labour Party.

Extract from What makes St Sidwell’s Point such an asset. Source: Exeter Labour Party.

Both Ian Collinson’s reports contain an assessment of the risks the council faces in closing Northbrook pool. These include “potential loss of members, reputational damage to the council due to the closure, and the challenge of accommodating current block and club bookings at other facilities”. It then claims that a series of measures will reduce these risks.

These include “offering seamless access to other leisure centres” and encouraging “continued engagement and loyalty” from pool users to ensure they “feel valued and supported during the transition”.

The council will also “maintain open, honest, and timely communication with all members and users” as it closes the pool, “emphasising the advantages of alternative facilities”. It says a “transparent and empathetic approach will help build trust, reduce uncertainty, and foster a positive experience during the change” which will be promoted by a “well-structured communications campaign”.

It adds that “if” demand at other leisure centres increases because of the closure, it will “consider” adding “additional temporary sessions”, while it hopes people will “transition to other centres without a significant disruption to their routines”.

Put together these amount to a mix of ignoring the barriers identified by the public consultation, trying to convince pool users they will be better off without it, and committing the council to doing little, if anything, once it is shut. Echoes of the closure of Clifton Hill sports centre abound.

Rather than reducing these risks the council’s approach may well make things worse, as so many already believe so little the council says about Northbrook.

As the Save Northbrook Pool campaign puts it, addressing councillors directly: “You have so many choices when it comes to funding Northbrook. If the decision is made to close it, we as local taxpayers and voters can only conclude that there is something else we are not being told.

“Coming on top of so many poor decisions about other leisure centres – the Pyramids and Clifton Hill – it will erode our belief in future Exeter City Council decisions even further.”

Northbrook pool campaigners demonstrate outside Exeter Guildhall

Northbrook pool campaigners demonstrate outside Exeter Guildhall

The council sees things differently. Ian Collinson’s reports say the decision to close Northbrook pool “will align with the council’s corporate plan by contributing to a well-run council”.

His recommendation to tomorrow evening’s executive committee meeting is that the pool should be permanently closed, apparently regardless of the outcome of this evening’s scrutiny meeting.

His report to tomorrow’s meeting contains only a few differences from his report for this evening.

It says that Northbrook pool “requires on-going subsidies to continue operating” without making clear this is true of all the council’s leisure centres. It says the “significant costs” of keeping Northbrook open “vastly outweigh” the pool’s income, without substantiating either claim.

In his scrutiny committee report he also offers a flat denial: “On 25 February 2025, the council took a decision to set a balanced budget. No decision was made to close Northbrook swimming pool.”

He adds: “However, a range of measures were identified where savings could be made across leisure services, including this facility.”

He then claims that any decision to keep Northbrook open would mean “financial implications in other service areas as further savings would need to be found”.

But both cannot be true at the same time. If the decision to close Northbrook pool was not taken in February, all the council’s executive committee would now need to do is select one or more of the other measures that the council claims it had already identified to make up the leisure service budget cuts.

Further savings would not now need to be found in order to keep Northbrook open.

As the monitoring officer reminds the executive committee, its members must “make a decision by weighing up the competing factors concerning the council’s equality act obligations against the financial pressures driving the recommendation to close the leisure facility”.

For the avoidance of doubt about who is responsible, he adds: “Members are required to carefully consider the legal, equality and financial implications of the proposals in order to reach a decision”.

As the Save Northbrook Pool campaign points out, making an informed decision about the future of Northbrook pool without a more complete and accurate understanding of its day-to-day operating costs, membership and marketing, maintenance and capital investment requirements, and without placing them in the context of wider leisure services capital expenditure, is difficult if not impossible.

So much so that to make a decision to close the pool without such an understanding could be so unreasonable as to make it liable to be quashed on judicial review.

What then of Duncan Wood, the councillor responsible for leisure services, claiming – when trying to defend the huge running costs of the £44 million St Sidwell’s Point – that the only way to approach the service-wide challenges facing the council is to look at leisure services costs as a whole?

Ian Collinson’s approach is to consider Northbrook pool in isolation. If he adopted the same approach to St Sidwell’s Point, would he recommend its closure too?